Read: Cocaine: A Short History

COCAINE: A SHORT HISTORY

Coca is one of the oldest, most potent and most dangerous stimulants of natural origin. Three thousand years before the birth of Christ, ancient Incas in the Andes chewed coca leaves to get their hearts racing and to speed their breathing to counter the effects of living in thin mountain air.

Native Peruvians chewed coca leaves only during religious ceremonies. This taboo was broken when Spanish soldiers invaded Peru in 1532. Forced Indian labourers in Spanish silver mines were kept supplied with coca leaves because it made them easier to control and exploit.

Cocaine was first isolated (extracted from coca leaves) in 1859 by German chemist Albert Niemann. It was not until the 1880s that it started to be popularised in the medical community.

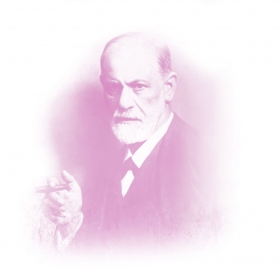

Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who used the drug himself, was the first to broadly promote cocaine as a tonic to cure depression and sexual impotence.

In 1884, he published an article entitled “Über Coca” (About Coke) which promoted the “benefits” of cocaine, calling it a “magical” substance.

Freud, however, was not an objective observer. He used cocaine regularly, prescribed it to his girlfriend and his best friend and recommended it for general use.

While noting that cocaine had led to “physical and moral decadence,” Freud kept promoting cocaine to his close friends, one of whom ended up suffering from paranoid hallucinations with “white snakes creeping over his skin.”

He also believed that “For humans the toxic dose (of cocaine) is very high, and there seems to be no lethal dose.” Contrary to this belief, one of Freud’s patients died from a high dosage he prescribed.

In 1886, the popularity of the drug got a further boost when John Pemberton included coca leaves as an ingredient in his new soft drink, Coca-Cola. The euphoric and energizing effects on the consumer helped to skyrocket the popularity of Coca-Cola by the turn of the century.

From the 1850s to the early 1900s, cocaine and opium-laced elixirs (magical or medicinal potions), tonics and wines were broadly used by people of all social classes. Notable figures who promoted the “miraculous” effects of cocaine tonics and elixirs included inventor Thomas Edison and actress Sarah Bernhardt. The drug became popular in the silent film industry and the pro-cocaine messages coming out of Hollywood at that time influenced millions.

Cocaine use in society increased and the dangers of the drug gradually became more evident. Public pressure forced the Coca-Cola company to remove the cocaine from the soft drink in 1903.

By 1905, it had become popular to snort cocaine and within five years, hospitals and medical literature had started reporting cases of nasal damage resulting from the use of this drug.

In 1912, the United States government reported 5,000 cocaine-related deaths in one year and by 1922, the drug was officially banned.

In the 1970s, cocaine emerged as the fashionable new drug for entertainers and businesspeople. Cocaine seemed to be the perfect companion for a trip into the fast lane. It “provided energy” and helped people stay “up.”

At some American universities, the percentage of students who experimented with cocaine increased tenfold between 1970 and 1980.

In the late 1970s, Colombian drug traffickers began setting up an elaborate network for smuggling cocaine into the US.

Traditionally, cocaine was a rich man’s drug, due to the large expense of a cocaine habit. By the late 1980s, cocaine was no longer thought of as the drug of choice for the wealthy. By then, it had the reputation of America’s most dangerous and addictive drug, linked with poverty, crime and death.

In the early 1990s, the Colombian drug cartels produced and exported 500 to 800 tons of cocaine a year, shipping not only to the US but also to Europe and Asia. The large cartels were dismantled by law enforcement agencies in the mid-1990s, but they were replaced by smaller groups—with more than 300 known active drug smuggling organisations in Colombia today.

As of 2008, cocaine had become the second most trafficked illegal drug in the world.